When the term Brutalism is mentioned in Birmingham, the mind often jumps to the old Central Library or the Chamber of Commerce House. Yet, this bold architectural style penetrated far deeper into the fabric of the Second City, leaving behind a legacy of concrete structures, many of which have, until now, escaped the wrecking ball.

The Precarious Future of Concrete Icons

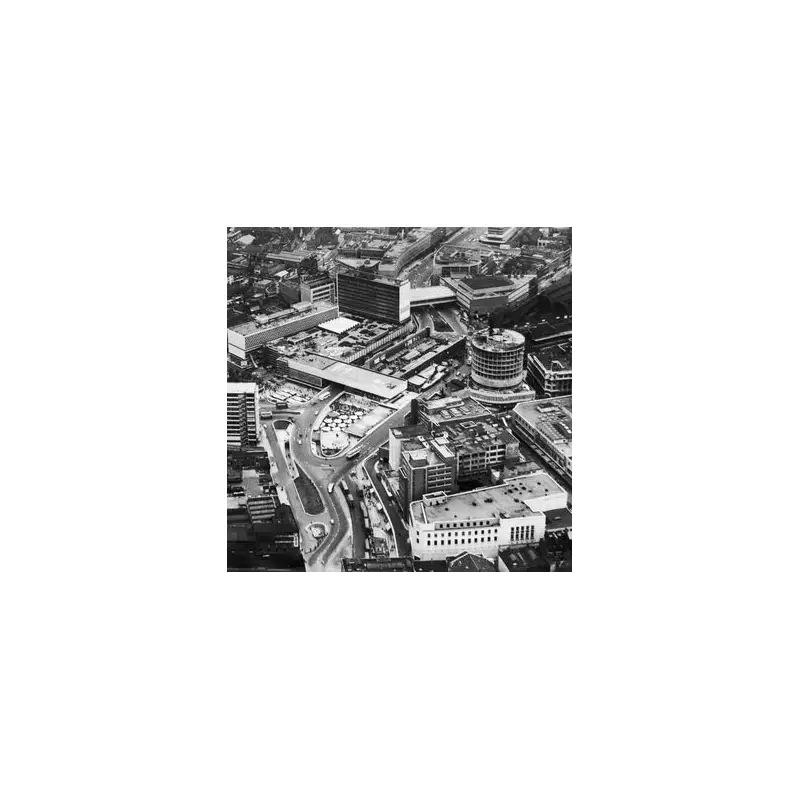

A closer examination reveals a landscape where numerous Brutalist buildings have already been lost. Those that remain are increasingly living on borrowed time. A prime example is The Ringway Centre on Smallbrook Queensway, one of the last major standing structures of its kind in Birmingham. Its fate appears sealed after city planners voted for its demolition to make way for area redevelopment, though campaigners continue their fight to save it.

Like the divisive spread Marmite, these buildings inspire strong opinions—you either love them or hate them. As their numbers dwindle, the debate over their value and preservation only intensifies.

The Architects and Their Enduring Marks

The story of Birmingham's Brutalism is heavily intertwined with key architects, most notably John Madin. His portfolio includes the iconic Birmingham Central Library, completed in 1974, which Prince Charles once infamously described as looking more like "a place where books are incinerated, not kept." Madin also designed the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce House in Edgbaston, Quayside Tower on Broad Street, and the Redditch Library.

Another significant figure was James A. Roberts, the visionary behind both The Rotunda and the soon-to-be-bulldozed Smallbrook Ringway Centre. His work, alongside Madin's, defined the city's post-war ambition and modernist skyline.

A Gallery of Lost and Threatened Landmarks

The roll call of significant Brutalist sites in and around Birmingham is a poignant mix of the demolished, the repurposed, and the endangered.

Buildings that have already fallen include:

- The AEU union building on Smallbrook Queensway, demolished in 2005 after 50 years, now the site of the Radisson hotel.

- The BBC Pebble Mill studios, which closed in 2004.

- The original Bull Ring Shopping Centre, opened in 1964.

Other notable surviving structures, each with an uncertain future, encompass:

- The Birmingham Post & Mail tower.

- The Adrian Boult Hall at the Birmingham Conservatoire.

- One Hagley Road in Edgbaston.

- The former PowerGen site in Shirley.

- The NatWest Tower at 103 Colmore Row.

- Tricorn House in Edgbaston, designed by Kaye Firmin and Partners in 1976.

- Neville House on Harborne Road.

- The Birmingham Repertory Theatre on Broad Street, designed in 1971.

- New Street Station's signal box, dating from 1965.

- The ATV Alpha Tower, constructed alongside the Central Library at Paradise Circus.

These buildings, from civic libraries and office blocks to theatres and signal boxes, represent a transformative era in Birmingham's history. Their raw concrete forms were symbols of progress and urban renewal in the post-war decades. As the city continues to evolve and reinvent itself, the remaining Brutalist edifices stand as stark, imposing reminders of a recent past, their continued existence a subject of passionate discussion and, for some, a race against time.