Scientists have uncovered a startling effect of predator calls on migrating birds, revealing that the familiar hoot of the tawny owl causes robins to significantly cut back on their night-time feeding.

The Night-time Threat

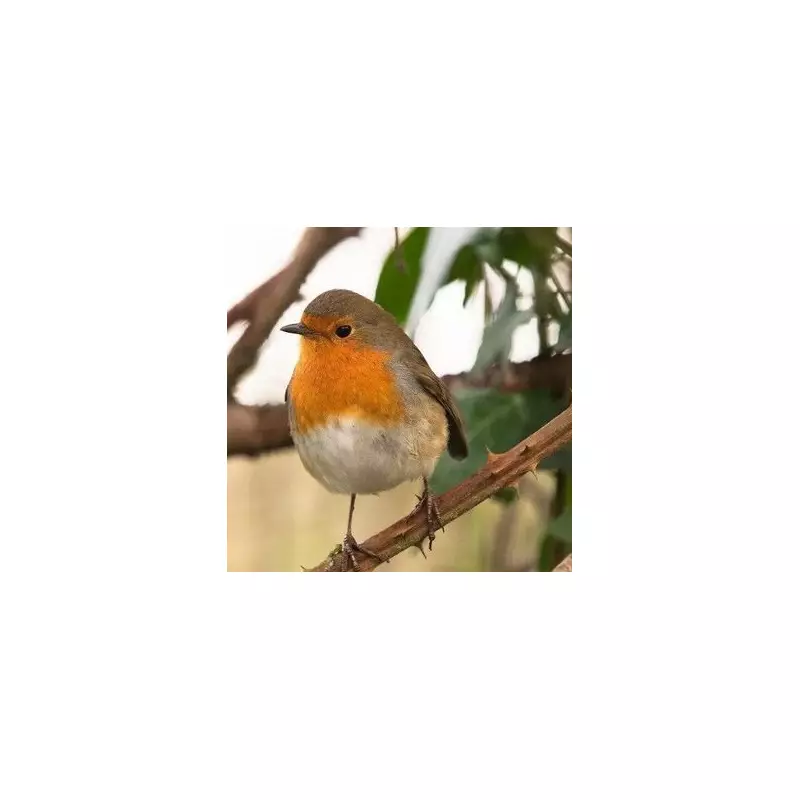

The research, conducted by a team from Sweden's Lund University and published in the Journal of Animal Ecology, demonstrates for the first time how the mere sound of a nocturnal predator can alter a bird's energy-gathering behaviour. Professor Susanne Åkesson led the study, which focused on young robins embarking on their first southward autumn migration.

During this arduous journey, the birds make essential stopovers to rest and refuel. However, each pause presents a danger, as predators may be close by. The study aimed to understand how the perception of threat influences the robins' crucial feeding routines.

Clear Results from Predator Calls

The experiment exposed the migrating robins to recorded calls from two different birds of prey: the diurnal sparrowhawk and the nocturnal tawny owl. The findings were unambiguous.

The call of the sparrowhawk had little effect on the robins' behaviour. In stark contrast, the hoots of the tawny owl triggered a strong reaction. Upon hearing the owl, the robins immediately became more vigilant, reduced their overall activity after dark, and most critically, ate less food.

"For the first time it has been possible to show the calls of nocturnal predators affect how birds obtain energy during their migration," explained Professor Åkesson.

Consequences for Survival and Breeding

This behavioural shift has direct and serious physical consequences. By eating less, the robins accumulated fat reserves at a slower rate, leading to a measurable deterioration in their physical condition.

Professor Åkesson framed it as a stark trade-off: "to dare to eat and build up fuel reserves or steer clear to avoid being eaten." The reduced feeding forces the birds to extend their stopover time to replenish their energy adequately.

These extended stopovers create a cascade of potential problems:

- Delayed arrival at wintering grounds.

- Increased competition for the best territories, which are claimed by earlier arrivals.

- A subsequent negative impact on both overwinter survival rates and future breeding success.

The research highlights a previously underappreciated stressor in the already challenging life of a migratory bird. The acoustic landscape, filled with predator cues, directly shapes their health and prospects.

"By understanding how migratory birds respond to different threats, we can improve how we plan the design of stopover sites and peri-urban environments," Professor Åkesson concluded. "If birds have access to calm and protective surroundings during their stopovers, it increases their chances of surviving the long journey."