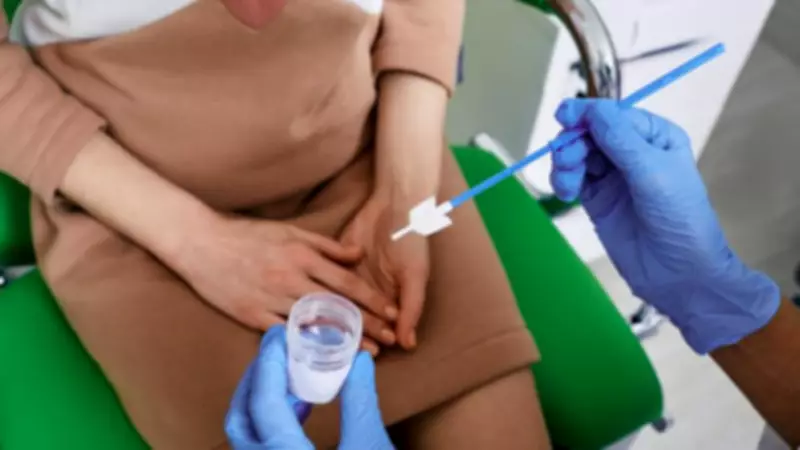

A groundbreaking new cervical cancer screening method that utilises menstrual blood collected on a sanitary pad could prove just as accurate as traditional smear tests, according to significant new research. This innovative approach tests period blood for the human papillomavirus (HPV), the primary virus responsible for most cervical cancers, potentially allowing women to conduct crucial screening at home without undergoing an invasive medical procedure.

A Potential Home-Based Alternative to Traditional Smears

Currently, the standard screening process in the UK involves a clinician taking a sample directly from the cervix using a small brush inserted into the vagina. While certain home testing kits exist in specific circumstances, they are not yet routinely available to the general population. This new method could dramatically shift that paradigm, offering a more accessible and less intimidating option for many.

Large-Scale Study Reveals Promising Accuracy

In a substantial study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ), researchers based in China conducted a direct comparison. They evaluated menstrual blood samples against clinician-collected cervical samples to assess how effectively each method detected cervical cell abnormalities that can lead to cancer. The research involved 3,068 women, aged between 20 and 54 with regular menstrual cycles, who were recruited between 2021 and 2025.

Each participant provided three distinct samples for analysis:

- A menstrual blood sample collected using a specialised sanitary pad and strip.

- A cervical sample taken by a clinician in the traditional manner.

- An additional sample processed directly by laboratory staff for further verification.

The researchers specifically measured how accurately the tests detected moderate to severe cervical abnormalities, known as CIN2 and CIN3, which typically require medical intervention. The results were highly encouraging. The menstrual blood test demonstrated a sensitivity of 94.7%, successfully identifying the vast majority of individuals who had the condition. This performance was comparable to the clinician-collected samples, which showed a sensitivity of 92.1%.

Understanding the Test's Specificity and Referral Rates

While the menstrual pad test was found to be slightly less specific, leading to a higher number of false positive results, a key metric remained strong. The likelihood that an individual with a negative test result truly did not have the disease was statistically identical for both methods. Furthermore, the rates at which patients were referred for more detailed follow-up testing were also similar between the two screening approaches.

Expert Conclusions and Cautious Optimism

The study authors concluded decisively, stating: “The results of this large-scale community-based study show the utility of using minipad collected menstrual blood for HPV testing as a standardised, non-invasive alternative or replacement for cervical cancer screening. The findings of this study support the integration of menstrual blood-based HPV testing into national cervical cancer screening guidelines.”

Sophie Brooks, health information manager at Cancer Research UK, welcomed the findings but emphasised the need for prudence. She commented: “It's encouraging to see research exploring new ways to make cervical screening more accessible. Testing menstrual blood for HPV is an interesting, non-invasive approach and could potentially offer another option in the future. But it's still very early days, and we need more research with larger and more diverse groups to understand how well it works for different people and whether it could fit into existing screening pathways.”

Brooks reinforced the vital importance of current screening, adding: “Cervical screening saves lives by helping to prevent cervical cancer from developing in the first place. Cancer Research UK encourages people to read their invite carefully and consider taking part.”

Addressing Barriers to Screening Attendance

Athena Lamnisos, chief executive of the women’s cancer charity The Eve Appeal, highlighted how this new method could assist individuals who find traditional screening procedures difficult or distressing. She said: “It's exciting to see new, more acceptable and potentially gentler ways of offering what could be a life-saving test to prevent cervical cancer from developing. The ability to test for HPV in menstrual blood isn't the answer for everyone though - people are eligible for screening until 64 and many will be menopausal. People have different barriers and concerns about screening, so being able to offer a choice of different methods could be very positive for some who are eligible for screening but don't currently attend.”

This research represents a significant step forward in women's preventative healthcare, potentially opening the door to more personalised and accessible screening options that could increase participation and, ultimately, save more lives through early detection and prevention.